How the Cities of The Office Illustrate America's Economic Divide

Why the Stamfords of the world thrive while the Scrantons stagnate

I’ve spent a lot of time in Pennsylvania and in Connecticut. But for reasons that will soon become obvious, I’d never visited either Scranton or Stamford, which you’ll recognize from the American version of Ricky Gervais’ hit show The Office. Given visiting small to mid-sized American cities is my only real hobby, and I’m a big fan of the first few seasons of the show, I figured it was time to visit.

I mostly expected to come back with a few observations about how the portrayals of the two cities in the show align with reality, but what I realized is the two cities are a convenient pairing to explain regional inequality in America. Strap in, this is going to be a long one.

As I’m sure most of you know, The Office centered on a branch of a struggling paper company, Dunder Mifflin. Competition from big box retailers like Staples meant that the company needed to get leaner. That included, eventually, consolidation.

Corporate was determined to close one of their branches. It came down to either Scranton, or the Stamford, Connecticut branch. This plot arc played out over the first three seasons, which also happened to be the show’s best.

Spoiler alert: corporate eventually chose to keep the Stamford branch, but after the manager leveraged his promotion to get a job at a competitor, Stamford won out. So Dunder Mifflin Scranton lived to fight another day. Rather, another six seasons.

It wasn’t just branch manager Michael Scott’s bizarre behaviour that put Scranton at a disadvantage. Scranton is also at a notable geographical disadvantage relative to places like Stamford.

Two towns, divided by geography

While the show hinted at the economic divide, and occasionally addressed some of the underlying causes, you could be forgiven for thinking they were just two random suburbs, one of which happens to be closer to New York (and on the water). It’s easy to get that impression, given that the show was filmed in California office parks. But this vastly understates the geographic divide.

Scranton is a relatively small, remote mountain town, 120 miles northwest of New York (and roughly the same distance to Philadelphia). Despite having a population of around 75,000, it’s the primary economic anchor of Lackawanna County (population: ~215,000). In other words, it’s the only economic game in town.

That anchor isn’t as strong as it once was. The city’s population peaked at over 140,000 in the 1930s, but the decline of the coal and textile industries dragged down the local economy. The city’s population stabilized in the 2000s, nearly 50 percent below its peak.

Stamford is an entirely different story. It’s nearly twice as large as Scranton, but, crucially, it’s part of the New York metro area, which is home to around 20 million people. In other words, it’s part of a labour market roughly 100 times larger than Lackawanna County. Size matters.

Cities and towns that are part large labour markets are better able to match people to jobs, and entrepreneurs to opportunities. There’s a good reason why even people who don’t like cities tend to cluster around them. Even the rise of hybrid work hasn’t really changed that.

You can see this divide in the data. Circling back to our two towns, the median household income in Michael Scott’s beloved Scranton, Pennsylvania is less than half as much ($48,776 vs $100,718) and the poverty rate is nearly twice as high (19.6 percent vs 10.1 percent) as his rival branch’s city, Stamford, Connecticut.

It’s not hard to see why. It’s much easier to attract and retain talent in a prosperous, centrally located city than a former coal town hours away from major cities. While the theme wasn’t necessarily explored in detail, it was there to see.1

Economic fortunes can diverge for many reasons. I don’t claim to have a definitive answer to why Stamford is doing better than Scranton. But geography matters. While infrastructure can help shrink geography (more on that later), communities in large labour markets have a major advantage in attracting people and investment.

Now, let’s get into some of my highly subjective observations from my visit. A few days isn’t a substitute for actually living somewhere, so I don’t claim that my observations are in any way definitive. But visiting the two cities really brought home the value of commuter rail in particular.

Stamford, CT

Stamford is only 40 miles from New York Penn Station. You can get there in 54 minutes on the Acela train. In other words, it’s within commuting distance of the center of global commerce.

Getting to Stamford was a breeze for me. Quick hour and 45 minute from Billy Bishop to Newark, took the air train to the Amtrak station, then it was an hour and 27 minute ride. Only real slowdown was at Penn Station, where the crew switched over and 300+ people boarded (sold out train). Most cities would beg for that kind of connection to a major international airport. It's like if you could get a train from Kitchener to Pearson. Yeah, you should be jealous. Look at all that leg room!

Arriving in Stamford, it’s clear that you’ve left the City. But it’s not like the train spits you out in the country either. The Amtrak station is just south of downtown, albeit separated by two highways. The station feels like a central hub for the city, rather than just an afterthought, as is often the case with North American rail stations. Though, as you can see, the station is oriented a little more around passengers arriving by car rather than pedestrians.

My first stop was Harbor Point, a pleasant mixed-use community just south of the station. I was planning to meet a friend from the City at Third Place by Half Full Brewery. Nice place, surprisingly good beer for a brewery in New England.2 As I was sipping on a taster flight, I got a text from my friend. He got stuck in Manhattan. I wasn’t fussed. I’d just meet him in the City later. Bought a $13 Amtrak ticket to Penn Station, carried on with my day. God I love commuter rail!

Harbor Point is clearly on the up and up. There are many new mid-rise apartments, and many more under construction. That should come as no surprise, given that it’s an hour away from Penn Station, and right by the water.

I wasn’t in the neighbourhood just for the beer or to gawk at surprisingly expensive apartments. I was there to visit the Dunder Mifflin Stamford office. Well, maybe not The Office per se. But the building they used for the external shots of the Stamford branch (333 Ludlow Street). It’s about a fifteen minute walk to the station, so you could clock out at 5pm and be in Manhattan for dinner at 6:30. Not a bad location.

As you can see, the area’s pretty quiet after hours. I was curious what the view from the office looks like after re-watching the third season. Copyright restriction wouldn’t allow me to take a screenshot of Jim Halpert’s new office view after he relocated from Scranton to Stamford, but if you fast forward to the 4:48 mark of Season 3, episode 1, you get a nice look. as Jim put it: “you can’t beat that view.”

Of course, that isn’t the real view. In fact, it looks suspiciously like an ocean view from, say, California - which is precisely what it is. As you might have guessed, the reality wasn’t so grand. Don’t get me wrong - it’s charming. But not exactly breathtaking.

Now, I kind of assumed that wandering around taking pictures of Dunder Mifflin Samford was a normal thing that people do. After all, the show has a big fanbase and it takes ten seconds of Googling to find the location. Apparently, it was unusual. A very nice security guard wandered outside to see why I was lurking around.3 He hadn’t seen the show and wasn’t aware of the connection. I guess I’m the only weirdo who’d bothered to make the pilgrimage lately. Maybe I do need better hobbies.

My next - and most important - destination should come as no surprise to any of you who knows me well. Pizza. Or, more accurately, Apizza. Connecticut’s contribution to America’s regional pizza culture. New Haven style pizza is considered one of the very best pizza styles in America. To my surprise (and delight), Sally’s now has a location in Stamford. Having previously waited multiple hours for a spot at their New Haven location, it was kind of nice to just walk in. Was it as good as the original location? I dunno. It’s hard to be objective about these things. It feels a bit more special when you’re at the original location. It was delicious, and that’s all that counts.

I can definitely see the appeal of Stamford. It’s just big enough that you’ve got most of the amenities you need, but small enough that you can drive around without too much trouble. Not quite a big city, but not quite a suburb. It’s a happy medium that will certainly please some, if not everyone.

The appeal of Stamford really came into focus midway through the third season of the show, as the two branches merged and some Stamford employees were offered the opportunity to relocate.

Jim Halpert: “You’d actually move to Scranton?”

Karen Filippelli: “Yeah, if they’d let me. I think I would.”

Jim: “New York City is 45 minutes down the road from here…and you want to move to Scranton. I dunno. If I were you, I’d move to New York.”

This illustrated the tradeoff, but I think undersold it. As we discussed, you don’t actually need to move to New York to take advantage of New York amenities. Western Connecticut is so well connected that you can visit every weekend. Scranton, by contrast, is not well connected to New York, Philadelphia, or anywhere. At least not by rail.

As fans of the show know, Karen followed Jim to Scranton, along with four of her Stamford branch colleagues. This was the least realistic part of the show. No one is moving to a small city in Pennsylvania to work for a failing paper company. In real life, they’d take the package and get a new job in the New York metro area. That, admittedly, would not make great television.

Scranton, PA

One unfortunately programming note. It rained most of the time I was in Scranton, so I don’t have as many photos as I’d like. Most notably, I didn’t manage to get a shot of the Penn Paper building that you’ll recognize from the credits. But I think I managed to get a good flavour of the city, which I rather enjoyed.

We’ve already established that geography isn’t as kind to Scranton as it is to Stamford. Scranton is three times as far from New York, and there isn’t another major economic anchor it can latch on to. Infrastructure can help shrink geography. But there isn’t even an Amtrak line at the moment. The Scranton-New York route was cancelled in 1970. However, there are plans to bring it back.

Scranton looks close enough to New York on a map. Indeed, it isn’t that far. It’s 122 miles west of Penn Station. That’s almost exactly the same distance as Kingston to Ottawa - a drive that few would think twice about. But with New York metro area congestion, it’s no joke. The drive through the Bronx is soul crushing. I’m rarely in a car within the boundaries of New York City, since getting around is easier by transit. Since there is no transit option, we had no choice. I can’t imagine anyone doing this drive unless they absolutely have to.

We arrived in Scranton without much of an agenda. I wanted to get a flavour for the city, but I didn’t know much beyond some scattered Office references.

One thing I was curious about was the old Amtrak station. I knew it still existed, but not where it was. As we arrived at our hotel, I saw it: the train station is the hotel now. No joke. I accidentally booked myself a night at the old train station.

The hotel is gorgeous. Much of the station is still in tact. The old benches are used as seating in the common spaces. It feels a bit haunted at night, though that might have been because when I asked about the history of the hotel the front desk clerks informed me that the place is haunted.

Keeping with the haunted and potentially murdery old hotel vibe, the hotel has an old cocktail bar that, if primed by ghost stories, might seem a bit like the bar from the Shining. It was quite lovely, assuming it wasn’t a merely a haunted delusion.

The bar is adjacent to the tracks. The old chandeliers are in place. It’s everything a train nostalgic could want, apart from the trains.

Speaking of trains, Scranton has two train museums that share the same parking lot: the Steamtown National Historic Site and the Electric City Trolley Museum. Believe if or not, Scranton was a streetcar pioneer. Nowadays, there is no rail passenger city of any kind in the city. For now. You may recall that one Joseph R Biden hails from these parts, and Amtrak Joe is pretty keen on reconnecting smaller cities to passenger rail.

The lack of passenger rail was somewhat surprising to me. Equally as surprising was the presence of streetcars in Scranton, operating or otherwise. I didn’t realize that Scranton was home to the first North American streetcar, which operated until 1954. Today, well, they seem to have some buses. But not much in the way of a mass transit system. Sigh.

Despite the dearth of mass transit, the city is surprisingly urban. While Stamford has many blocks downtown that feel like blocks adjacent to downtown in a relatively large city, Scranton feels a bit like its own city. I chalk that up to the remoteness, and the fact that it urbanized in a time when passenger rail was the default intercity transportation method. Parts of the core feel very much like they could be within the New York Metro area.

I had a pretty good time in Scranton. Stamford had more amenities obviously tailored to an urban guy in his 40s. But Scranton had its own character. There’s the bar adjacent to the old rail tracks. The Barcade imitation arcade bar that serves an “Italian Wedding Ramen,” or the various working class downtown bars that haven’t existing in most big cities since the 90s.

My favourite example was a bar my friend and I rendezvoused after I went to Cooper’s (more on that later). I was trying to keep myself to two drinks a night, since it was a long trip and I wanted to return home in good shape.

I was nursing my second glass of orange juice. A man who looked like a former linebacker who’d just finished a factory shift entered my orbit. He had two glasses in his hand, and was cheersing everyone. I kept my gaze ahead to avoid contact. No such luck.

The man eventually got our attention. He made some vague pleasantries as I sized him up. Could I take him down if I have to? I had theories. He seemed nice enough, though.

How’s yer night?

Good…good.

Whatcha drinkin’?

I’m taking it pretty easy.

Rumpleman’s!

Sorry…

Rumpleman’s! I’ve had like forty of these tonight.

The bartender looked at me like I wasn’t the first guy roped into this conversation.

Bartender! Three double Rumpleman’s!

I didn’t know precisely how my plans were about to be derailed, but the fix was in.

Ah. Rumple Minz. A peppermint schnapps. I stared at the plastic cup in my hand and thought about the life choices that lead up to this moment. I suppose there are worse fates.

We all took the shot. It wasn’t bad. Our new friend was pleased. I was mysteriously feeling a little better about my quasi-sobriety. He was fun. Couldn’t make heads or tails of who he was, given his state. But he managed to carry himself alright for a guy with a belly full of schnapps.

Eventually he took off, as though he was punching out from a shift. That was that. On to the next place for him, I assume. Godspeed.

Had I learned something from this interaction? Had I been initiated into some ancient Appalachian ritual? Maybe he was just a nice guy with interesting tastes. Probably nothing learned here. Oh, well. On to the next place.

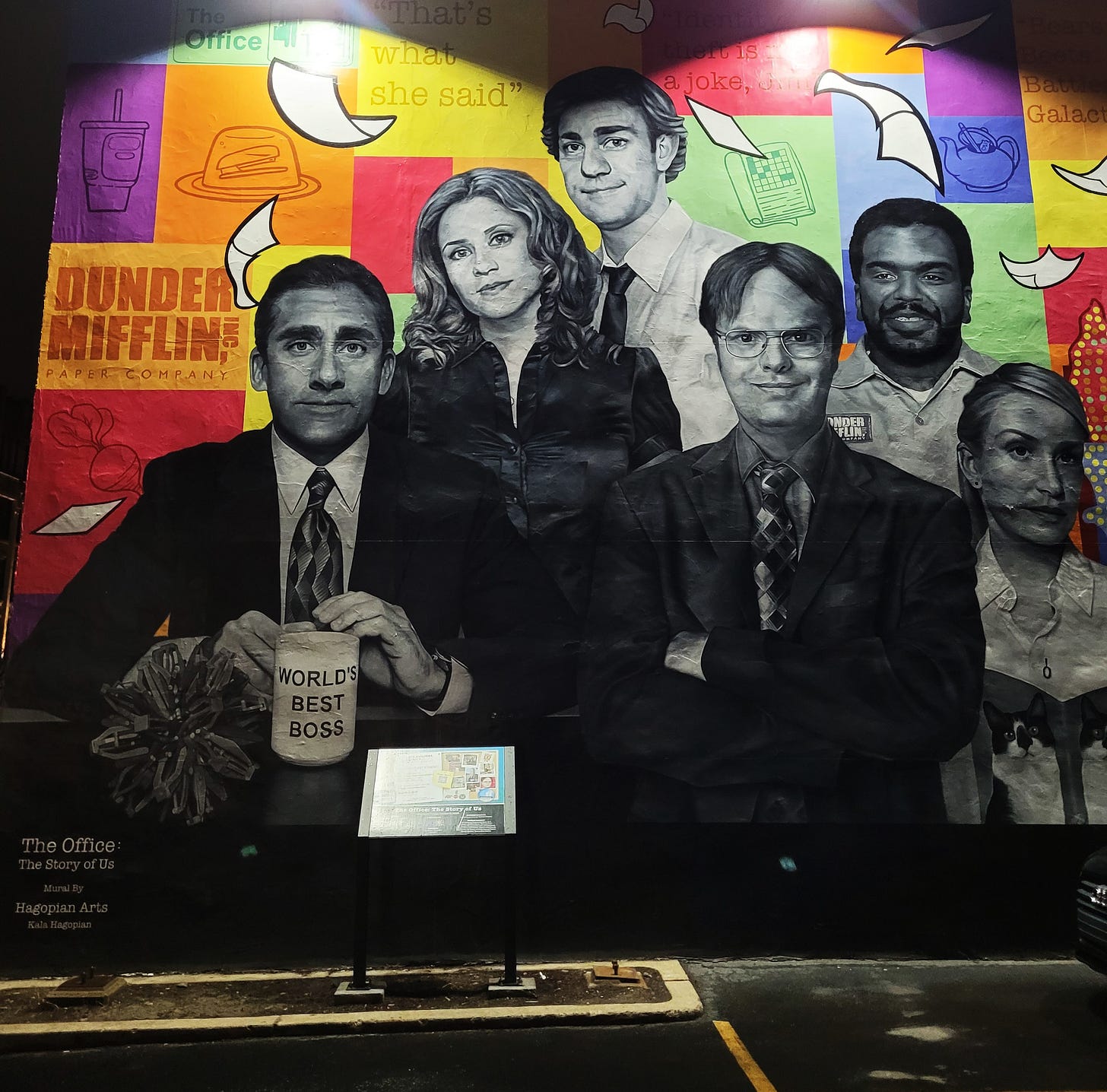

Our destination that night was Cooper’s. It’s a kitschy looking seafood place that got a few mentions on the show. My suspicion is that it has only survived because of the show. It’s a bit space, meaning they need to do a lot of volume. And old school seafood restaurants aren’t exactly on trend. Indeed, they leaned into the show. They have multiple references to the show posted inside and outside.

As much as it looks like a tourist trap - and clearly markets itself to tourists - it’s good. Whether it’s a chowder or a plate of shrimp scampi, you’re going to leave happy. It’s a reminder of the value of tourism. Something in short supply there. Something made more difficult by the lack of rail access.

One of the great things about infrastructure is that it can, in some cases, make up for geography. Think of the Erie Canal, for instance, which connected Western and Central New York to New York City. Without it, we’d never have heard of Buffalo, for instance. Geography can shrink distances, creating opportunities further from the great centers of commerce.

Amtrak plans to do just that, albeit on a limited scale. They plan to provide three daily round trips between Scranton and New York, which should come in at about 3:25. Certainly useful for occasional travel, but not a reasonable commuting distance. Still, under 3.5 hours to New York beats the total flight time from most places west of Chicago. If there was a three and a half hour train from Toronto to New York, you better believe I’d used it. It takes longer than that to get to Ottawa, and I do that trip regularly.

Even if it’s not a reasonable daily commuter distance, the new Amtrak line should make living in Scranton a more viable option for some. If you need to be in the City now and then, but not every day, having the option to get the train in and out a few times a month might be enough. Given the extreme discrepancies in housing prices between much of the New York metro area and Scranton, this could unlock some badly needed reasonably affordable housing. It’s not free - the estimated capital cost is $2.9 billion, with an annual operating budget of $87 million - but you’d be shocked to know how much governments are willing to spend on far less useful projects.

Of course, there’s some skepticism. Steamtown is adjacent to the likely location for the Amtrak stop. It on the rail line and adjacent to the bus depot. So, by process of elimination, this is probably it (unless they plan to reposes the hotel).

I happened to bump into a man who worked for one of the rail companies. I asked him about the Amtrak project. He chuckled. It wasn’t the first time there were rumours of a new Amtrak service. I told him there is actual funding attached to it this time. He told me he’d believe it when he saw it. Fair enough.

Turning around smaller cities outside of major metro areas isn’t easy. But having the right infrastructure is a necessary, if not sufficient condition. Not everyone wants to use the train, but if you want to give people access to high paying urban jobs and attract new residents who are tethered to those jobs, people need options. No one would bat an eye at spending $3 billion on a new highway. No reasons the government can’t provide basic train service.

Scranton will probably never be Stamford (sorry, Michael). But better connection to the New York metro area should help shrink the income gap with the New York metro area, at least a bit. I hope, anyways.

A microcosm for America’s small cities

What really fascinated me about the two cities is how clearly they captured the divide between small cities within and outside of major metropolitan areas. This is often portrayed as a gap between the coasts and flyover country, but in reality, proximity to any major city - whether it’s New York or Oklahoma City - is a major economic advantage.

One challenge that is somewhat unique to American cities is that the country is dotted with old single industry towns, much like Scranton, whose primary industry no longer exists. They’re often remote, and their infrastructure was oriented more towards regional than national or global trade. That makes participating in a global economy oriented around major hubs and ports challenging.

One potential answer for some of these cities is finding ways to plug into bigger economies. That might mean slightly better infrastructure to make periodic trips easier, or perhaps becoming attractive destinations for people with niche interests, or flexible workers who would be happy to live in a smaller center in exchange for a lower cost of living. None of these will turn Scranton into Stamford. But they could be part of the puzzle.

Of course, we often get caught up in discussions of talent attraction, rather than providing a good quality of life for existing residents. I’m at least as guilty as the next person. But for declining towns, attracting and retaining people is crucial. If towns like Scranton are going to preserve their quality of life, they need to maintain a stable tax base. If you can’t staff the paper company, you’re going to run into trouble.

Finding creative ways to stabilize smaller, more remote communities is one of America’s central challenges right now. America operates on easy mode. It’s the world’s dominant economy. They can afford to make a lot of mistakes and still create an immense amount of wealth. The trouble is, much of that wealth finds its way to a few major metropolitan areas. Americans need to find a way to help more communities participate in the new economy. Because no matter how well the broader economy is working, leaving behind large swaths of people can bring a country to dark places.

That’s a bit of a pessimistic note to end on, especially for someone who is extremely optimistic about America’s future. But rather than try to drag this to a cheerful conclusion, I’ll just leave you with a fun video of Scranton’s second most iconic landmark. You’re welcome.

I would argue they even underplayed the economic discrepancy between the two cities.

Yeah, that was mean. But I’m bitter that New England style IPAs have largely crowded out traditional West Coast IPAs. Bitter + translucent > juicy + hazy.

Someone could have pitched this as an Office episode. Dwight is alarmed to see a photographer lurking around the premise and ambushes him with bear spray. Instant classic.